MYANMAR: ‘RECKLESS’ SHIPMENTS OF JET FUEL CONTINUE AS AIR STRIKES MULTIPLY

Lunes, 8 de julio de 2024

- Data reveals shipments of jet fuel still arriving in Myanmar

- Investigation shows military air strike killed 12 civilians and injured 26 as historic monastery in Magway, Central Myanmar attacked

- “My friends were killed right before my eyes on the street,” eyewitness tells Amnesty

Amnesty International has documented new shipments of aviation fuel to Myanmar despite global calls to deprive the country’s military of the resources it needs to carry out unlawful air strikes.

In January 2024, Amnesty International exposed the Myanmar military’s new evasive tactics for importing aviation fuel throughout 2023, following sanctions imposed on parts of its supply chain.

That pattern continues with at least two, and likely three, additional shipments of aviation fuel having entered the country between January and June this year. As with the previous shipments identified by Amnesty International in January, the fuel was bought and sold multiple times before reaching the last leg of its trip in Viet Nam ahead of shipment to Myanmar.

In two instances, the Chinese owned HUITONG78 oil tanker transported fuel from Viet Nam to Myanmar. Other companies appear to have played a role in the supply chain too, including fuel traders Singapore-based Sahara Energy International Pte. Ltd. and Chinese state-owned entity (SOE) CNOOC Trading (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. A likely third shipment, also by HUITONG78, appears to have come to Myanmar from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in May 2024.

It is unclear how the fuel was used after it arrived, but the military’s control of the port means there are significant risks it could be used for non-civilian purposes.

“The Myanmar military is relying on the very same Chinese vessel and Vietnamese companies to import its aviation fuel, despite Amnesty International having already exposed that reckless supply chain,” said Agnes Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International.

“It is a raw display of both the sheer impunity with which the Myanmar military is operating, and the utter complicity of the states responsible, including Viet Nam, China and Singapore.”

Air strikes on the rise

In June 2024 the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar reported that military air strikes against civilian targets in Myanmar have increased five-fold in the first half of this year.

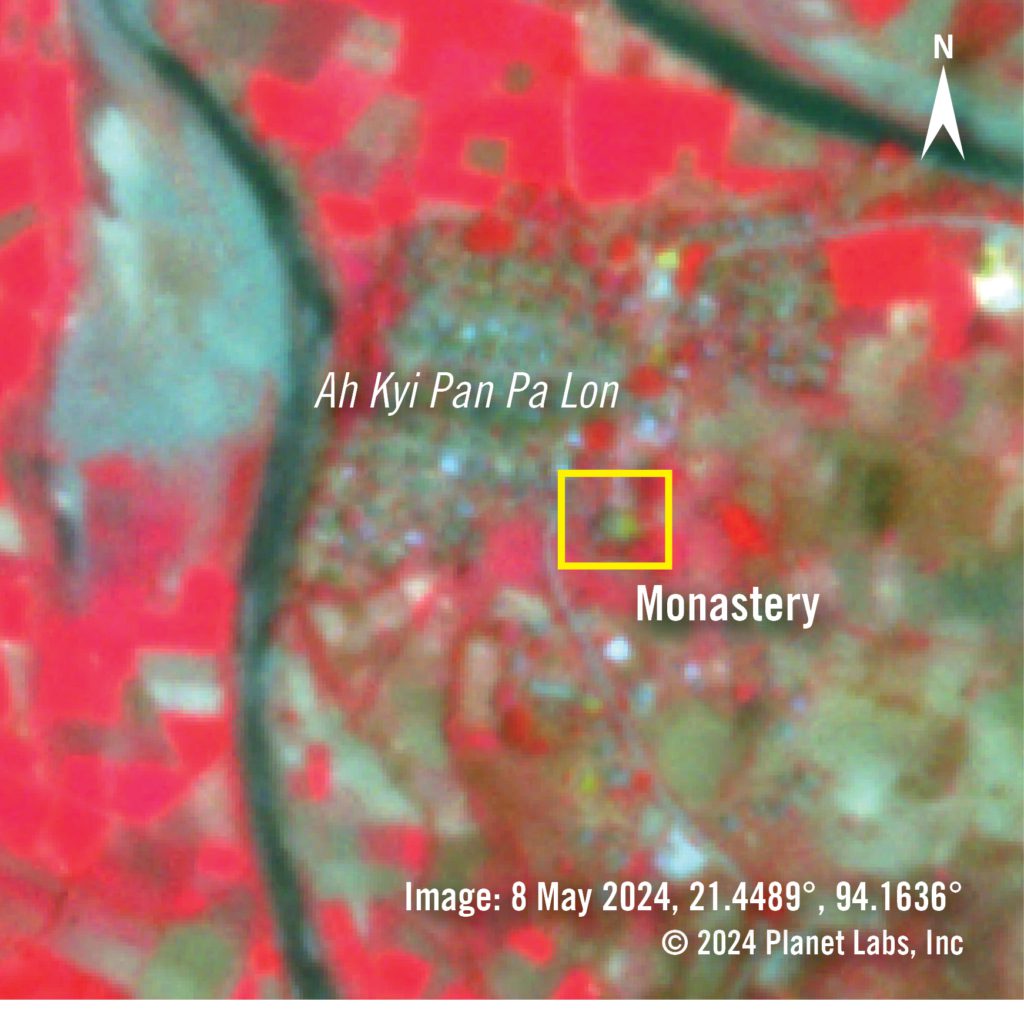

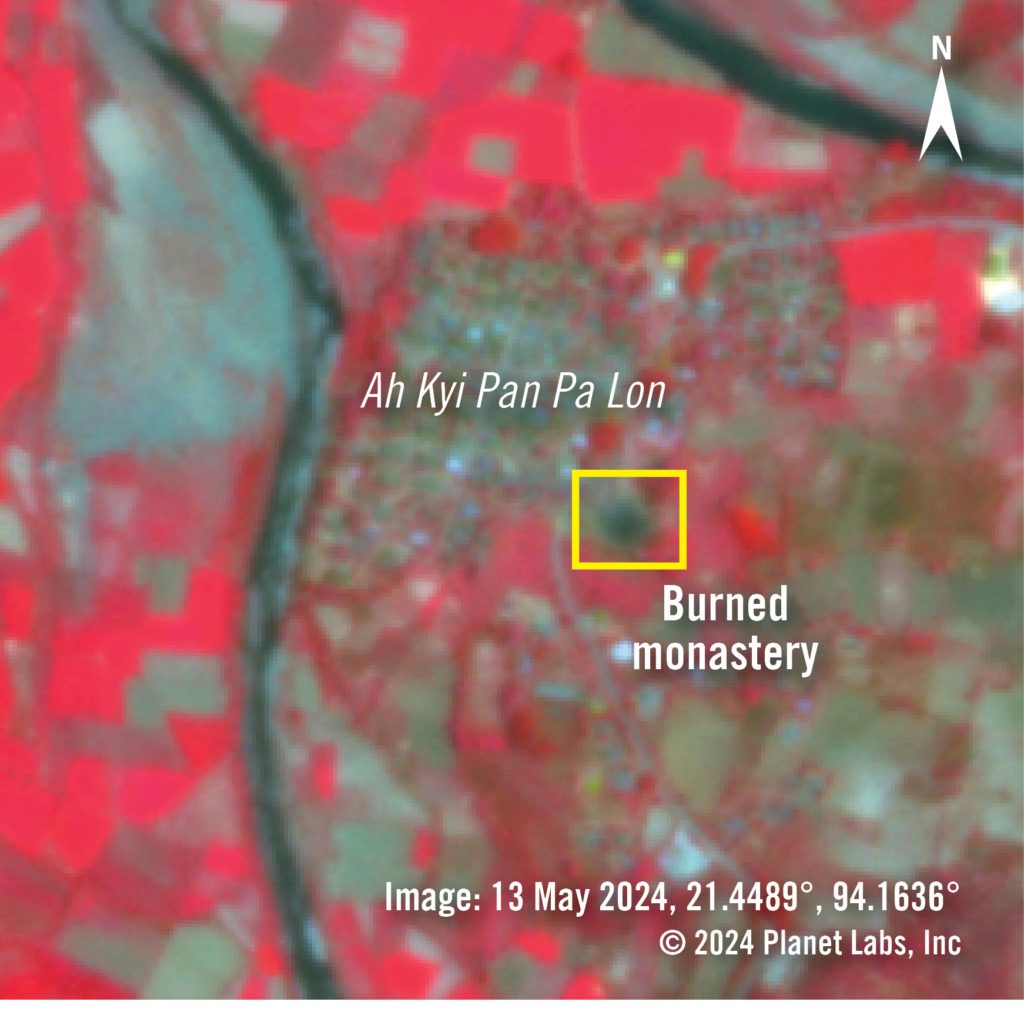

Amnesty International documented one of these attacks. Witnesses told Amnesty that on the morning of 9 May, the Myanmar military launched an attack on a monastery in Saw Township’s Ah Kyi Pan Pa Lon village in central Myanmar’s Magway Region.

Following two initial air strikes, witnesses said that a fighter jet then circled back around and followed up with heavy gunfire directed at those fleeing the initial explosions.

The monastery, which is believed to be roughly 100 years old, was destroyed.

Amnesty International interviewed four survivors of the attack in Magway and one person who arrived at the scene afterwards to help the victims. Researchers also analysed 34 photos showing the corpses of victims, wounds of survivors, weapons used in the attack and the extent of the damage.

All the visual evidence of the destruction of the monastery is consistent with an air strike that caused a fire and severely burned both the structure and many of the victims. Photos of fragments of the ordnance used show the remnants of a tail kit for an aerial bomb, as well as unexploded 23mm High Explosive Incendiary (HEI) ammunition that is fired from the GSh-23 machine gun mounted as pods on fighter jets such as the Russian YAK-130.

The date on the discarded cartridges from the 23mm HEI rounds indicate the ordnance was manufactured locally in Myanmar in 2024. The wounds of other victims of the attack are consistent with fragments from aircraft bombs or direct gunfire. Satellite imagery also shows that the monastery area has been heavily burned.

‘I heard the people screaming’

Saw Township is located in a contested area of central Myanmar, where parallel administrative structures and armed groups known as People’s Defense Forces (PDF), which sprang up after the coup to resist the military alongside the civilian National Unity Government (NUG), are active.

Witnesses said that while some PDF forces known as People’s Defense Teams, or Pa Ka Pha in Burmese, were present at the monastery, the majority of people were civilians. They also said there had been no fighting in or close to the village before the air strike.

In the early morning of the attack, witnesses said they heard buzzing in the skies, which they described as sounding like a drone. Some hours later, about 50 to 60 locals had gathered on the first floor of the monastery to discuss their concerns about transport issues, including taxation and routes.

In addition, witnesses reported that at least one child and the head monk of the monastery were on the second floor of the site, a place where computer classes were sometimes held.

According to survivors, who asked to be anonymous for fear of being targeted further by the Myanmar military, the first bomb dropped at around 10:45am.

“The bomb fell a bit far behind me, right into the place where my brother, uncle and sister were sitting,” one man said. His relatives were killed instantly.

“I am sure that the fighter jet aimed at killing all of us,” he said.

Following the first bomb, he said the monastery started to collapse and people were trapped under the falling debris.

He managed to escape the site: “Within a few minutes […], I saw the jet come again to the monastery, and this time another bomb was dropped that set the main building on fire,” he said.

Another man said he escaped from the monastery unharmed following the first bomb. He was hiding across the road when the second bomb was dropped. He saw the monastery ablaze. A fighter jet then started to shoot at people running away.

“I heard the people screaming in the monastery. Some people were running on the street amid the continuous gunfire from the fighter jet,” the man said. “The fighter jet flew over the monastery and opened fire on the people running around. I witnessed my friends being killed right before my eyes on the street.”

Those killed in the air strike included a child, while the head of the monastery was among the injured, according to a list of victims given to Amnesty International by a rescue worker.

Even if members of the Pa Ka Pha were present in the monastery at the time of the attack, the pilot should have known there could be civilians as well. Thus, the shooting of civilians attempting to flee and the bombing of a site of religious, cultural and historical value suggest the attack was indiscriminate. It should be investigated as a war crime.

“This recent attack joins a rapidly growing list of violations of international humanitarian law in Myanmar including air strikes, ground raids, arbitrary detentions, torture and numerous other violations targeting civilians,” Callamard said.

How Myanmar continues to access aviation fuel

Amnesty International and others have called on companies and governments to suspend jet fuel shipments to Myanmar or risk complicity in a deadly supply chain. But as these new findings show, many are still not listening.

Vessel tracking and trade data show that the Chinese oil tanker HUITONG78 transported two shipments of aviation fuel to the former Puma Energy terminal (now controlled by the Myanmar based Shoon Energy group and the Myanmar military) in Thilawa, Yangon port, on 14 January and 29 February, respectively. In common with all shipments identified by Amnesty International in 2023, the oil tanker picked up the fuel at the Vietnamese Cai Mep Petroleum storage terminal operated by Hai Linh Co. Ltd., before departing for Myanmar.

Also like the 2023 shipments, the 2024 shipments involved multiple purchases and resales of the same fuel, making it hard to trace the original supplier. In regard to the January 2024 shipment, before its arrival in Viet Nam, the fuel can be traced to the Vopak Singapore Banyan Terminal, a storage facility controlled by Dutch storage and logistics company Royal Vopak. Royal Vopak confirmed the shipment but emphasized that “[o]ur service is the safe storage of our customers’ products while it is in our terminals in the ports” and that they “respect applicable laws, regulations and sanctions”.

The February 2024 shipment can be traced back to the BP Hua Dong terminal in Ningbo port, Hangzhou Bay, China. Amnesty International was unable to identify the company that controls the Chinese terminal.

Before the final transfer and sale of fuel to Myanmar, the January shipment was sold to a Vietnamese company by the Singapore branch of the global fuel trader Sahara Energy. The February shipment was sold by the Singapore trading branch of Chinese SOE China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC Singapore). In both cases, customs data shows that Sahara Energy and CNOOC Singapore should have been aware that the fuel was transported to Viet Nam for transit purposes only. Each of the shipments was worth approximately USD 8 million.

Suspicions raised over third shipment

Evidence also indicates there was likely a third shipment of aviation fuel to Myanmar, in May 2024.

According to vessel tracking data, the HUITONG78 onloaded fuel at the Hamriyah port in Sharjah, UAE, in April, arriving at the Yangon port on or about 12 May. The vessel appears to turn off its AIS radar as it enters Thilawa port, during which satellite imagery shows what appears to be the HUITONG78 moored at the former Puma Energy terminal in Thilawa.

The vessel’s draught data (which indicates a change in overall weight of the ship) suggests that it offloaded fuel at the Thilawa terminal. Although Amnesty International was not able to confirm whether the fuel was in fact aviation fuel, it is quite likely the case given the pattern of shipments conducted by this same vessel.

The HUITONG78 vessel is registered for Protection & Indemnity (P&I) insurance with the West of England P&I Club, although in response to Amnesty International, the Club stated that “if […] this vessel was carrying jet fuel to Myanmar, then there was no cover for those trades”.

It’s high time that companies put an end to these shipments.

Agnes Callamard, Secretary General at Amnesty International

According to the P&I Club, the HUITONG78 is owned by an affiliate of the Chinese state-owned defence company China Aerospace Science and Industry Corp (CASIC). According to a media report, CASIC has been involved in transporting US sanctioned Venezuelan oil.

“While Amnesty does not know for certain how the aviation fuel shipped in this way was used once it arrived in Myanmar, the risk is high that the military – which controls the terminal where the fuel was offloaded – uses it to fuel attacks against civilians. It means shipping and fuel companies have no option but to withdraw from that supply chain completely,” Callamard said.

“That includes everyone involved, from vessel owners to insurers to fuel traders. It’s high time that companies put an end to these shipments.”

All companies named in these findings were contacted for comment. The only companies to respond were Royal Vopak and West of England P&I Club.

Tags: MYANMAR, HUMAN RIGHTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION.