PROSECUTED FOR DEFENDING THE ENVIRONMENT: ACTIVISTS AND COMMUNITIES STAND UP TO PROTECT OUR PLANET

Viernes, 7 de junio de 2024

Por: Graciela Martínez, Senior Campaigner, Libertad de Expresión, México y Honduras, Oficina Regional para las Américas, Amnistía Internacional, y Cristopher Isaí Cruz Ordóñez, Jefe de Campañas y Comunicación, Amnistía Internacional México

What happened to the defenders from Colonia Maya?

Five leaders of the residential community Colonia Maya in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas have been facing criminal charges since 2018 for peacefully protesting against a housing development in a mountainous area near where they live. The five leaders are Elizabeth del Carmen Suárez Díaz, Eustacio Hernández Vázquez, Lucero Aguilar Pérez, Martín López López López and Miguel Ángel López Martínez.

A group from Colonia Maya—made up of mothers, Tsotsil and Tseltal people, children and youth— began to oppose the construction project because the developer had cut down around 100 trees that had helped slow run-off from rainstorms. The project had also started work without environmental or social impact assessments. In 2015, the deforestation on the ecologically protected mountainous area caused a flood that destroyed over 20 houses, a primary school and a kindergarten.

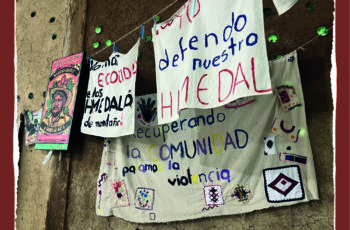

To draw attention to this situation, the people of Colonia Maya organized peaceful, creative and educational actions, like the ‘March of the Benches’, where children, teachers, and others acting in solidarity marched carrying school benches to point out how the flood had made it impossible for school to continue.

Photographs of the Colonia Maya residential community in southern Mexico, in Chiapas. Photo © Martín López López y Elizabeth Del Carmen Suárez Díaz

The authorities halted the housing development and made recommendations, but the developer decided to continue. In 2017, sympathizers organized a peaceful protest with banners and cordoned off an entryway to symbolically block machinery. A company representative immediately reported them to law enforcement, and the prosecutor’s office issued warrants for the arrest of the five leaders for the crime of kidnapping in 2018.

Since then, the five Colonia Maya residents have been facing criminal charges, despite the lack of evidence against them, in what appears to be a tactic to stifle dissent and peaceful protest by threatening jail time. They could go to prison at any moment.

Why is protest important for environmental advocacy and climate justice?

Peaceful protests, especially on the streets, have been essential tools for opposing and bringing attention to resource extraction, energy, and infrastructure projects that have polluted or harmed the environment or violated other human rights. These protests have also been a key way to voice demands for climate justice, especially when authorities have long ignored them.

Around the world, climate activists and defenders of land, territory and the environment have exercised their right to protest in socio-environmental conflicts arising from urbanization or resource extraction. These protesters have demanded respect for their rights to self-determination; free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples; a healthy environment; information; and participation in projects that may affect the environment. They have also protested losses of culture and quality of life.

SIGN THE PETITION!

SIGN THE PETITION!In Mexico, people defending land, territory and the environment face serious risks.

ACT NOW!In many countries, the authorities have responded by repressing these protests, which violates defenders’ rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and freedom of association.

Demonstrators, especially leaders, suffer reprisals that range from surveillance to stigmatization to arbitrary detentions. At times authorities use excessive force or suppress the right to peaceful assembly to end protests related to land, the environment, or climate justice. Some governments have even enacted laws that criminalize protests.

In rural areas, there have been attempts to turn people off their land when communities’ titles are not officially recognized or when the boundaries of Indigenous Peoples’ ancestral lands are not clearly marked.

What is the Escazú Agreement and how can it help protect environmentalists?

The Escazú Agreement is the first binding treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean to address protections for environmental human rights defenders and the crisis they face. This agreement is backed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean and entered into force three years ago.

Latin America and the Caribbean is the world’s deadliest region for environmental defenders, but less than half of the countries in the region are party to the treaty. Some of the countries that have not yet committed to the agreement have some of the world’s highest numbers of killings of environmental defenders: Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras and Peru.

The Third Conference of the Parties to the Escazú Agreement (COP3) was held in Chile from 22 to 24 April 2024. This biennial event is the treaty’s most important decision-making forum, and during it the States Parties adopted the Action Plan on Human Rights Defenders in Environmental Matters. Now they must put it into practice to counteract the grave danger that environmentalists and climate activists face, even when protesting peacefully.

Tags: HUMAN RIGHTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, DDHH.