Contracted workers in Amazon warehouses in Saudi Arabia were deceived by recruitment agents and labour supply companies, cheated of their earnings, housed in appalling conditions and prevented from finding alternative employment or leaving the country, Amnesty International said today.

A new report, Don’t worry, it’s a branch of Amazon, shows how Amazon failed to prevent contracted workers in Saudi Arabia from being repeatedly exposed to human rights abuses, despite receiving complaints directly from workers about their treatment over a lengthy period of time. In many cases, it is highly likely that the abuses suffered by workers amounted to human trafficking, given the deception that occurred during their recruitment, and the exploitation endured once they were there.

“The workers thought they were seizing a golden opportunity with Amazon but instead ended up suffering abuses which left many traumatized. We suspect hundreds more endured similar appalling treatment. Many of those we interviewed suffered abuses so severe that they are likely to amount to human trafficking for the purposes of labour exploitation,” said Steve Cockburn, Amnesty International’s Head of Economic and Social Justice.

It is highly likely that the abuses suffered by workers amounted to human trafficking.

Steve Cockburn, Amnesty International’s Head of Economic and Social Justice

“Amazon could have prevented and ended this appalling suffering long ago but its processes failed to protect these contracted workers in Saudi Arabia from shocking abuses. Amazon should urgently compensate all those who have been harmed, and ensure this can never happen again.

“The government of Saudi Arabia also bears a heavy responsibility. It must urgently investigate these abuses and reform its labour system to guarantee workers their fundamental rights, including being able to freely change employers and leave the country without conditions.”

Amazon must urgently compensate all those who have been harmed, and ensure this can never happen again. The government of Saudi Arabia also bears a heavy responsibility.

Steve Cockburn

The report is based on information collected from 22 men from Nepal who worked in Amazon’s warehouses in Riyadh or Jeddah between 2021 and 2023, and who were employed by two third-party labour supply contractors – Abdullah Fahad Al-Mutairi Support Services Co. (Al-Mutairi), or Basmah Al-Musanada Co. for Technical Support Services (Basmah).

Names of interviewees have been changed to protect their identity. Amnesty International has shared details of the investigation with Amazon, Al-Mutairi and Basmah, as well as the Saudi Arabian government. Amazon’s responses can be accessed here. The others have not responded.

To secure work at Amazon’s facilities in Saudi Arabia, the interviewees, with one exception, paid recruitment agents in Nepal an average of US$1,500. Some took high-interest loans to pay the fees.

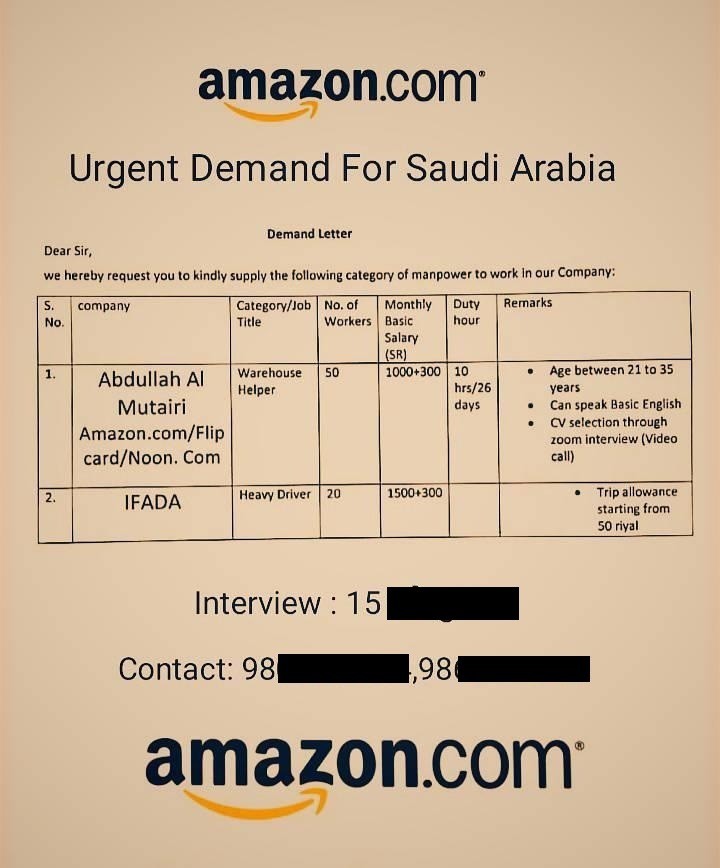

During the recruitment process, the agents, sometimes in collusion with the Saudi Arabian labour supply companies, deceived many of the workers into believing they would be employed directly by Amazon.

Some workers began to suspect that Amazon was not their direct employer when they received their contracts and documentation just hours before they were due to fly, but having already paid recruitment fees felt they had no choice but to continue.

Others realized only after arriving in Saudi Arabia.

I realized it was a different company on the day of the flight…I saw on my passport it said, ‘Al Basmah Co.’ but the agent said, ‘don’t worry, it’s a branch of Amazon’.”

Bibek, a worker.

One interviewee, Bibek, said: “I realized it was a different company on the day of the flight…I saw on my passport it said, ‘Al Basmah Co.’ but the agent said, ‘don’t worry, it’s a branch of Amazon’.”

In Saudi Arabia, the workers were mostly housed, for months, in dirty and overcrowded accommodation, sometimes infested with bed bugs. They were put to work in Amazon warehouses, but the contractors often withheld part of their salaries and/or food allowances without explanation, and underpaid overtime.

In the warehouses, workers said they were repeatedly required to lift very heavy items, ran to meet gruelling performance targets, were constantly monitored, and not allowed to rest adequately. In some cases this resulted in injuries and illness. One worker said he suffered a suspected broken arm and was signed off work for a month by a doctor, but because the supply company denied workers sick pay he felt that he had to resume work within two weeks.

Most workers signed two-year contracts with the labour supply companies but many spent less than 12 months at Amazon’s facilities before the work ended, which some likened to being “fired”.

The supply companies then moved these ‘jobless’ individuals to even worse accommodation, stopped paying salaries, and in some cases food allowances. Without any social protection or support from the Saudi state, some survived by eating bread and salt, and drinking salty water.

One worker, Kiran, said the accommodation “was extremely dirty. No air conditioning, no fans. The temperature was 50°C … There are so many workers … no beds, cooking gas or drinking water. There was no internet so we couldn’t contact our family.”

Most interviewees received no more work but the contractors took advantage of Saudi Arabia’s sponsorship system, or kafala, which despite some recent reforms binds foreign workers to their employers, preventing them from moving jobs without the employer’s consent and limiting their ability to leave the country freely.

The labour supply company managers refused to provide ‘transfer authorization’ documents required under Saudi regulations to allow workers to change employer within their first year. If workers left without permission, they risked arrest for ‘absconding’.

Many wanted to return home before their contracts ended but Al-Mutairi managers would not purchase the flight tickets they were legally obliged to provide, and told workers they would have to pay a ‘fine’ of between US$1,330 and $1,600 for exit papers.

As a result, the workers were stranded in appalling conditions at the mercy of the Amazon contractors.

A few contemplated suicide. Dev said: “I tried to jump from the wall, I tried to kill myself. I told my mum and she said ‘don’t, we will get a loan’. Already it is eight months since she took a loan and the interest is piling up.”

The vulnerability of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia was well documented before Amazon began operating there in 2020, and was identified in an Amazon risk assessment conducted in 2021, meaning the company knew about the high-risk of labour abuses in the country.

Workers began raising complaints directly with Amazon managers in Saudi Arabia in 2021, including by writing on dedicated white boards in the warehouses, or verbally at daily meetings, yet these were often ignored and the abuses continued into 2023.

One worker, Kiran said: “Amazon knows each and every problem we have with the supply company. Amazon asks workers about the problems and issues they face during daily meetings.”

Amazon knows each and every problem we have with the supply company.

Kiran, a worker.

Some workers who complained to Amazon were subject to reprisals by the contractors. One said salaries were deducted after complaints to Amazon about their living conditions. Another who complained to Amazon about the water quality in the accommodation said he was taken to a supply company office and pushed and slapped by an Al-Mutairi supervisor.

When he subsequently informed an Amazon manager about the assault, he said he was told “it’s not our business”.

The report finds that Amazon has contributed to abuses by failing to adhere to its own stated policies, or the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and potentially benefitted from the services of victims of human trafficking, as defined by international law and standards.

As well as compensating workers, the report recommends Amazon urgently investigates working practices across its facilities and supply chains, strengthens due diligence and ensures workers can speak out and be heard without fear of retaliation.

To better safeguard workers’ rights, it recommends Amazon hires more staff directly and reduces its reliance on labour supply companies, particularly when this poses a higher risk of abuse. When such companies are used, there must be much stricter controls to prevent abuse.

Amazon told Amnesty International that between March and June 2023 it conducted audits of Al-Mutairi and other contractors and found abuses consistent with our findings. Amazon said it recently hired consultants to review supply companies’ labour practices and remedy some abuses, including reimbursing the recruitment fees of those interviewed for this report, although to date none have received any money.

The proposed measures are important but come years after workers first raised complaints. More broadly, it is imperative that Amazon remediates all migrant workers who paid recruitment fees, and compensates them for the full range of abuses they suffered including those inflicted after they were ‘fired’ from the company, and those they reported facing in Amazon’s warehouses.

Steve Cockburn said: “It’s time for Amazon to finally put things right for workers who have suffered so much, and for Saudi Arabia to fundamentally reform its exploitative labour system.”

“It’s time for Amazon to finally put things right for workers who have suffered so much, and for Saudi Arabia to fundamentally reform its exploitative labour system.

Steve Cockburn

Tags: Migrants, Amazon, Human Rights.

Philippines: Former President Duterte’s arrest a monumental step for justice

Zimbabwe: Ten years without answers since activist Itai Dzamara’s disappearance

International Women’s Day: The world must resist attacks on gender justice

Global: Electric shock equipment widely abused by law enforcement agencies

Contact Us

Regional - Américas

Calle Luz Saviñón 519, Colonia del Valle Benito Juárez, 03100. Ciudad de México, México

Global

1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW. Reino Unido.